Last Wednesday, we experienced a weeks worth of headlines in a matter of minutes. Boom. European travel ban. Boom. Tom and Rita Hanks test positive for coronavirus. Boom. NBA season suspended. This series of events was simply another source of news fatigue that has made the past three months of 2020 seem even longer than 2019 in its entirety.

This is not the future we imagined when petitioning for 2020, but here we are three months in. We had a fun start in January, but I bet no one even remembers those days. Don't worry, here's a recap ...

Everything that happened in January is the past and while it may impact the future, presently, we have no idea what the rest of 2020 will bring.

Still, we'll make and shift plans. As humans, we design our lives around past, present, and future, but these are merely concepts that comfort us and help us maintain a semblance of order in life.

The truth is, time is an illusion. Because time has no objective frame of reference, our concept of time can be a deeply personal and subjective experience. This subjectivity is felt even more profoundly today given the meteoric rise of digital technology.

People will rarely agree about time more broadly, but what we can agree on, however, is the measure of time.

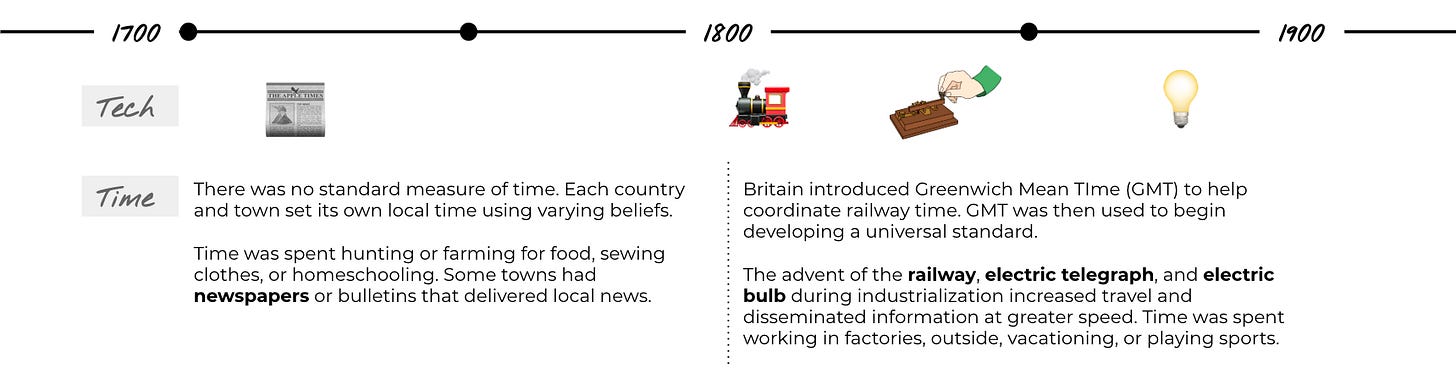

A super brief history of time

Did you know there was no formalized universal standard of time until the 1960s?

Before standardization, each country/town could have its own measure of time, which made cross-country communication, trade, and travel chaotic. The invention of railways in early 1800s exacerbated existing problems; travelers and goods were covering longer distances at a faster speed and people had to reset their watches as trains crossed various towns.

This led to regulation of time in mid-century Britain, what we now know as Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) based on observations of the sun. As the industrial age matured, so did the micro-management of time.

In late 1800s, the United States railway association helped standardize time into five time zones based on GMT. These time zones were enacted into law after WWI in 1918.

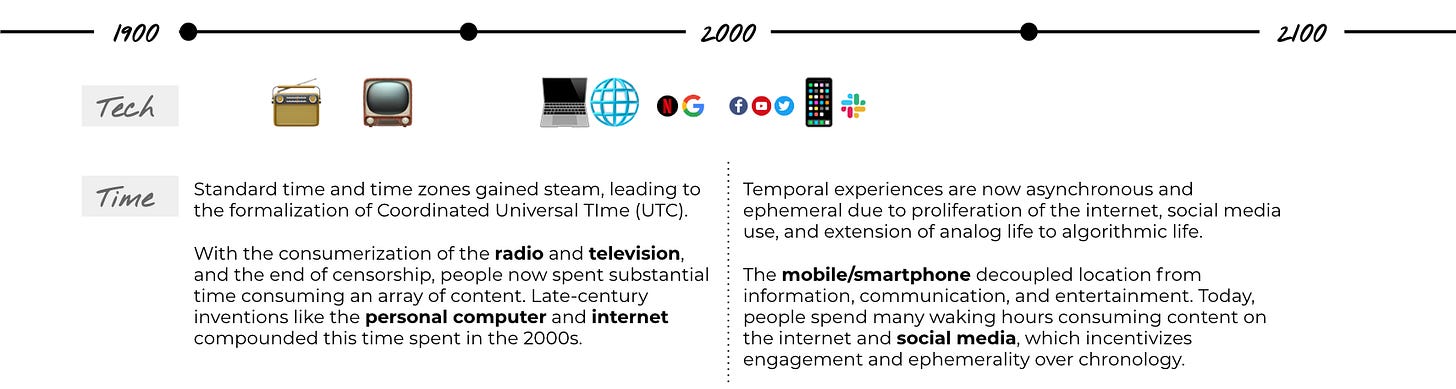

This brings us back to the universal measure of time, formalized in the 1960s. Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is based on the most accurate time standard, the atomic clock, and standardizes both analog and web standards.

People could set their own local times merely a century ago. Can you imagine? Without globalization and novel technologies, we could still live in our own lawless worlds with personalized interpretation of today versus tomorrow, or fast versus slow. I believe there exists elements of lawlessness today, despite the modern micromanagement of time. We’ll touch on that later, but first it’s necessary to contextualize technology’s impact on communication and media, and it's subsequent ramifications on time.

The evolution of time

Centuries ago, people had to be self-sufficient if they wanted to survive. Accordingly, people spent their waking hours hunting or farming their food, sewing their own clothes, or homeschooling their children. Their entertainment was found in nature, the arts, or sports.

Once the industrial revolution emerged in the 1700s, three key technologies disrupted time and how people spent it, particularly in the United States. The newspaper/printing press disseminated information, the telegraph expedited communication, and electric light extended daytime.

Early newspapers had limited content and audiences. Once printing press technology allowed mass production, the newspaper delivered actual reporting to all, meaning everyone knew current events across the country within weeks. People had more information than ever before. The world started to get smaller and faster.

When the electric telegraph went public in the 1840s, people could send text messages across long distances in mere minutes. Conversely, it could take a day to mail a letter from Philadelphia to New York City. Technology was creating new efficiencies, and subsequently accelerating time.

The most game-changing technology was the electric light bulb, invented in the late 1800s and a staple in most American homes by 1925. The lightbulb fundamentally changed how people spent their time; days became longer, more productive, and more enjoyable. With the light bulb, people could stay up longer to work, spend time with family, and enjoy leisurely activities.

So why does this matter? Even with these technologies, time spent was still uniform into the 1950s. People read their newspaper in the morning, went to work/school, and then came home to eat dinner, listen to the radio, and watch one of three television networks with family. People were doing similar activities and consuming similar content at the same time. This sense of order was shattered in the next decade.

The 1960s rise of mass media was ushered in by real-time news coverage, the end of artistic censorship, and the under-regulated FM radio. Contrarian ideas began spreading rapidly and young people developed unprecedented freedom. Concurrently, technological improvements in factories increased employment and discretionary income. More news and music, individualized identities, and money for an array of leisure activities signal the beginning of implicit fragmentation of time during the same decade time measuredly was formalized globally.

The 1960s are quite similar to present-time, but the internet has given us unprecedented global access to information and each other. With the invention of the mobile/smart phone, that access is instantaneous. Derek Thompson captured this new level of connectivity perfectly: "The radio set used to be a living room fixture. In order to listen to the radio, it was necessary to be at home. Then the car radio liberated the radio from the living room, and the television set replaced its corner of the living room. Then the smartphone liberated video from the television screen and put it on a mobile device that fit in people’s pockets."

Better technology means higher expectations. Keep up with current events and the latest TV shows. Be informed on social issues. Connect with friends frequently. Work harder and longer. Always be connected. These expectations have huge implications on how we experience time.

As I previously observed, there was distinction between work and social time a century ago. Once consumers adopted the internet and personal computer, these two worlds converged. You could be at work messaging friends, reading the news, or entertaining yourself with music. You could be at home reading and responding to work emails. People began consuming and processing more information. Unlike prairie times, periods of silence and boredom became rarer, making time feel like it was moving a bit faster.

Over time, digital companies realized the many hours of human attention they were capturing on the internet and wanted to commodify it. Enter algorithms. In 2006, Facebook introduced the News Feed. Suddenly, you could share status update with friends. In 2009, Facebook updated the sorting of News Feed from reverse chronological to popularity. It didn't matter when you posted content, substantial engagement could give you top rank.

This updated ranking blurred the lines between past and present; people began contextualizing content by popularity instead of time. In essence, all content was present-time because there was always something new to consume and there was a lack of archiving for the past. That was the plan; the newer and more interesting content was, the more time you would spend on Facebook, and the more money they made. The update also further individualized perspective of time since everyones feed was different. Thus began the lack of shared experiences, a characteristic of the early radio and television. Lastly, the update set precedence for other platforms by incentivizing virality and amplifying ephemerality.

The last decade has been the most defining and disorienting for my personal relationship with time. My first few years of using Facebook were enjoyable. There was continuity in the relationships I had, time was still linear, and content consumption was manageable. Once I traded in my BlackBerry for a smartphone in 2012, I discovered Snapchat. You're telling me that I could take dumb pictures and people could only see them for a few seconds? SIGN ME UP. I loved that app. Stories in particular reframed how I, and many others, viewed time. The transient nature of Stories emphasized the present at the expense of past or future. You had to be in the moment and friends had 24 hours to share in your experience. If not, they'd get FOMO because nothing was archived. Consume immediately or miss out—that's too much urgency for a social app.

After that, I fell in love with Twitter. There was, and still is, nothing more real-time than Twitter. I consider it a modern, democratized telegraph; anyone can send content to a global audience instantaneously. I've watched a lot of news break on Twitter. The flood of information can be thrilling but also fatiguing. Thanks to the Retweet, the global nature of the platform can feel like reading 50 local newspapers in a matter of hours.

Time couldn't feel faster given the amount of media I consume across Twitter, Google, streaming services, blogs, publications, and more, and I'm not alone. Neilsen found that American adults spend over 11 hours per day listening to, watching, reading or generally interacting with media in 2018. That's crazy. The world is exponentially smaller, louder, and faster today. I can't even remember everything that's happened in the last six months. The only thing I remember from the January recap video in the introduction is we still don't have Rihanna music.

High expectations due to technology extend to professional life. We are the most productive we've ever been. As I work remotely due to COVID-19, I can be reached through Gmail, Drive, Meet, Hangouts, Slack, Twitter, iMessage, WhatsApp, and by phone. Given a plethora of communication channels and processing power, even on mobile, being available and always working has become a badge of honor. This fosters a level of urgency and busyness that ties us to our calendars, which makes time feel like its moving faster for adults more than for children. It doesn't help that we're aging and time feels like it's running out.

Time isn't running out and it's not moving faster, people are simply in constant states of emergency.

Time is an illusion

Einstein said, "for us believing physicists, the distinction between past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion." I'm no scientist (yet) but I agree.

We've convinced ourselves that we are bound by minutes, dates, and deadlines. However, time is more relative than we think. Brian Greene, a theoretical physicist, explains it well. Imagine ... "If instead of being next to me, you were 10 light years away (and moving at about 9.5 miles an hour), what you consider to have happened just now on earth would include events that I'd experienced about four seconds later or earlier (depending on whether your motion was toward or away from earth). If you were 10 billion light years away, the time discrepancy would jump to about 141 years."

Time is an abstraction. It can move fast or slow depending on the individual. I believe that if people could universally experience time, there would be no distinction in past, present, or future. This eternalist view posits that past, present, and future are all real and exist equally. Basically, time is another dimension, like space.

Thanks to technology, we frequently experience the three states of time. As we live life, we are realizing the future. Yet, we also hold on to our past because social media gives us continuity with past friends/events. And of course, the present is a given. That makes life feel a little like this meme:

I believe three themes will continue to rise out of this disorder.

Commodification of Nostalgia. The past can be a source of comfort for people, a way to escape from present demands. We want to relive or continue happy moments. Drake has successfully tapped into nostalgia to maintain relevance for the last decade whether it’s tapping Degrassi costars for the I'm Upset music video or dropping an album of old leaked tracks aptly titled Care Package. More recently, Disney+ launched on the premise of nostalgia. For the first time, you can (legally) stream your favorite childhood cartoons and movies! Oh and there’s some new content too, in case you want to make new memories for later.

Focus on wellness. Higher expectations lead to more stress. People will continue to invest in wellbeing, both physical and mental, for longer and higher quality of life. On that note, did you know there’s a biological and chronological age? With this concept, if you improve your lifestyle and diet, you may decelerate your body’s aging. And if we go even a step further, maybe age will be classified as a disease in the future and scientists will find a cure. If we live forever, then time doesn’t really matter, does it?

Emphasis on Shared Experiences. On the content side, Netflix is leaning into a new (traditional) format by dropping three episode a week for some shows. Together, people can binge episodes weekly and experience key plot twists, creating zeitgeist unlike before. You don't have to be on Twitter to know this concept is (and will continue) working. Today, people have weaker ties and are more lonely than ever before. As people seek shared experiences, niche communities will continue to proliferate digitally and offline. If this unplanned, early adoption of remote work has taught us anything, it's that we need human connection and video is not enough. Events, communities, and gatherings will come back full force when the world returns to a healthier state.

COVID-19 is having catastrophic impact on the world and many of us are socially distancing to try to flatten the curve. I’ve noticed that, while working from home, the days are blending together with daylight as the only sign of time passing. Weekly habits like commuting, happy hour, and standard breakfast and lunch hours that served as time markers no longer exist. We’re becoming unstuck in time. We’re in a lawless world of breakfast for lunch, midday naps, and monwedsunday. Time is an illusion and I'm not the only one who feels it. We’re creating so many persistent memories at greater speed than ever before and are living a future few of us could have predicted. If you need to slow time a bit, don't forget to unplug and be bored.

Reality Bytes

💭 Thank YOU for reading. I'll keep this part short and sweet. Time is such a wild concept, but one I'm happy to discuss any time via email or DMs. If this conversation resonates with you, reach out (share this with others using the button above).

🎧 I'm late but Nao's Saturn is so so good. I listened to it throughout this essay, which took me a while to think and type thorough. Nao gives us range, 90s R&B vibes, AND afrobeats on this album. What more could you want?

📚 Lots of crypto books in my life right now. I enjoyed The Bitcoin Standard and would recommend, especially if you'd like to understand how bitcoin relates to the history of money.

🔅 Thank you for reading (un)real. If you’d like, you can subscribe here.